An Illustrated Guide to Eating a Lobster

Everything you need to know about the lobster, from cooking it to cracking it to making your own drawn butter.

Aug 03, 2021

Lobsters might seem challenging, what with those fearsome claws and the intimidating shell, but once you know how to handle them, you'll be able to fully enjoy one of the most versatile culinary ingredients from under the sea.

Today, lobster is a delicacy eaten as a main course, as a one-two punch with steak (aka "surf 'n' turf"), in lobster rolls at seafood shacks, raw in sushi or ceviche, and as a timeless comfort food in dishes ranging from lobster pot pie to luxurious lobster truffle mac and cheese.

A brief history of lobster eating

Lobster has a long and storied history as a source of nourishment and gustatory enjoyment. The crustacean makes an appearance in ancient Roman and medieval cookbooks, and are the focal point of feasts in paintings by 17th-century Dutch artists.

When European settlers came to North America, also in the 17th century, lobsters were hardly considered worthy of a first-class meal. Derided as “cockroaches of the sea,” the creatures were used as bait by Native Americans and only eaten when no fish could be caught. They were served to prisoners and servants through much of the 18th century, while Maine and Massachusetts wrestled with a glut of lobsters given their lowly status. According to author David Foster Wallace in his famed 2004 Gourmet magazine essay “Consider the Lobster,” “lobster was literally low-class food, eaten only by the poor and institutionalized.”

By the 1840s, commercial lobster fishing off the coast of Maine and technological advances in transporting fresh lobster helped popularize it, and for the next century, as transportation options improved and tastes evolved, lobster grew increasingly in demand, first as an inexpensive protein and eventually as a mainstay at American restaurants.

The post–World War II boom in America and the move away from wartime austerity saw lobster becoming a symbol of decadence for the upper middle class and the rich. Served in its shell for dinner, its meat dipped in rich drawn butter, lobster, along with steak, signified status. Upscale restaurants introduced live lobster tanks where diners could point out their unlucky main course, and in 1968 the first location of what would become Red Lobster opened in Lakeland, Florida.

Today people view lobster as an easy-to-prepare choice for a delicious meal or an ingredient that can elevate familiar dishes. It can add a briny burst to pasta, a toothsome bite to chowder, or, dressed in a bit of mayo, depth to a salad or sandwich.

A step-by-step guide to cracking a lobster

According to the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative (MLMC), which promotes the lobster industry around the world, breaking down a lobster for its meat is fairly simple. Here is an adapted step-by-step guide:

Step 1: Twist off the claws. This one's easy: Just use your hands to pull the claws from the crustacean and set them aside.

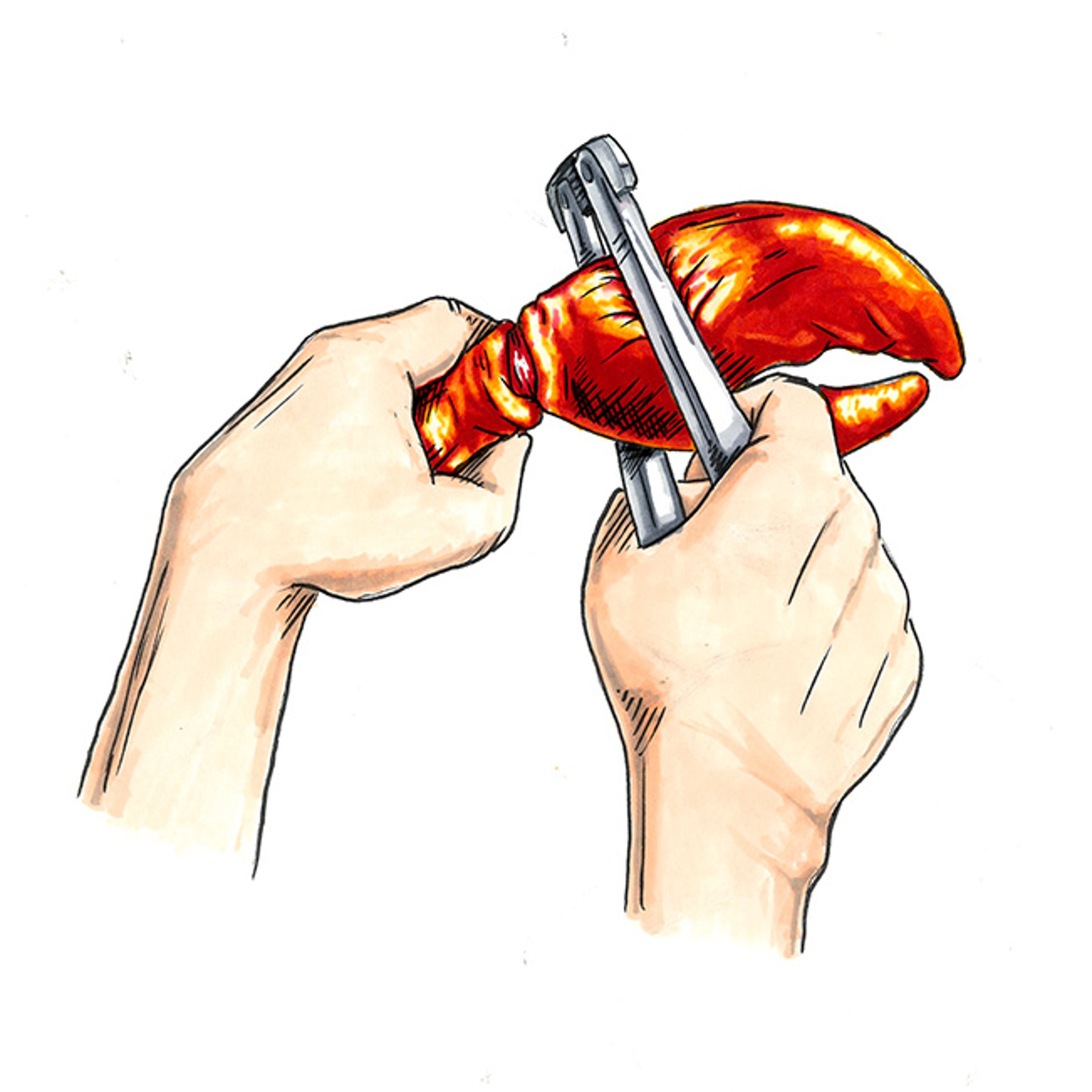

Step 2: Crack the claws and knuckles of the lobster with a nut- or lobster cracker, or go old-school and use your hands. Using a small fork or your fingers, pull the meat from the shell.

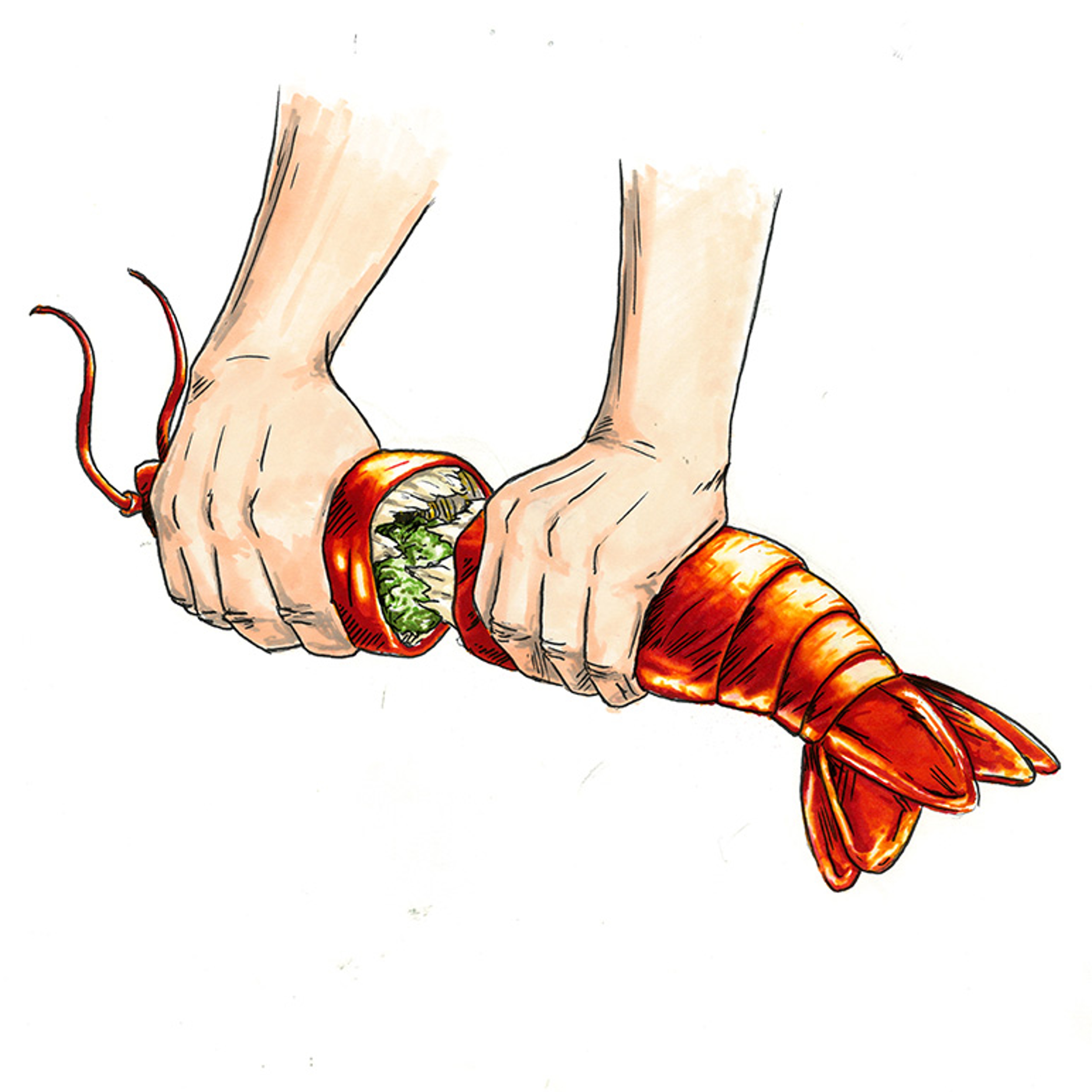

Step 3: Pull the tail away from the body, breaking the tail flippers. Next, extract the meat from each flipper.

Step 4: Use a small fork to push the tail meat out in one piece.

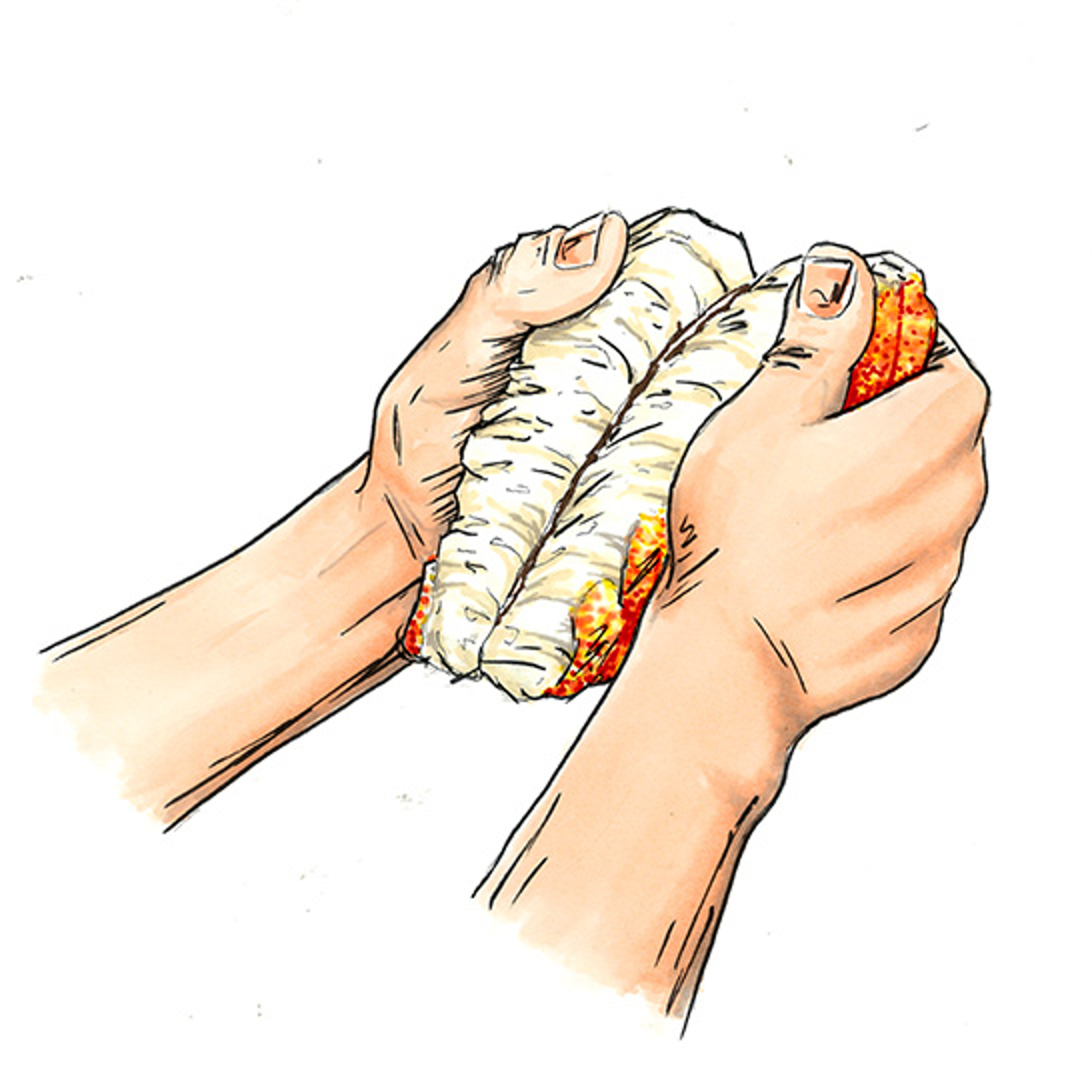

Step 5: Remove the black vein that runs along the tail meat, just as when you're deveining shrimp. Discard the vein.

Step 6: Turn the lobster over and separate the shell from the underside, pulling the two apart. MLMC recommends discarding the tomalley, though some consider it a delicacy (more on this below).

Step 7: Crack and open the underside in the middle using the nutcracker and fork. The small legs should be on either side. Extract the meat from the legs and joints using your teeth (being careful not to drip liquid all over yourself…which reminds us, don't forget the bib!).

Is it safe to eat the tomalley?

On the underside of a whole cooked lobster is a green mass known as the “tomalley." This is actually the crustacean's digestive gland, and it's comparable to a liver and pancreas. Its creamy texture and concentrated shellfish flavor make it appealing to lobster fans (and chefs, who use it in chowders and other briny dishes), but eating it does carry risks: For example, it can cause paralytic shellfish poisoning if a lobster ingested infected bivalves during a red tide. The Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about eating the tomalley back in 2008, but cases of infection from eating the gland are rare, and symptoms, such as nausea or headache, are usually minor.

Best and simplest ways to cook a lobster

Cooking a whole lobster is incredibly easy, once you get over the part about lowering it, alive, into a pot of salted boiling water. If you have a one-pounder, boil it in a large covered pot for 10 to 13 minutes (longer for larger lobsters), until it turns bright red.

Lobster tails are easy to cook too. Butterfly the tail by cutting through the shell on one side in a line down the middle. Pull the shell apart to help separate the meat on both sides, then press the meat back together. Next, place the tails on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper, brush melted butter over the meat, and cook under a broiler for about a minute per ounce.

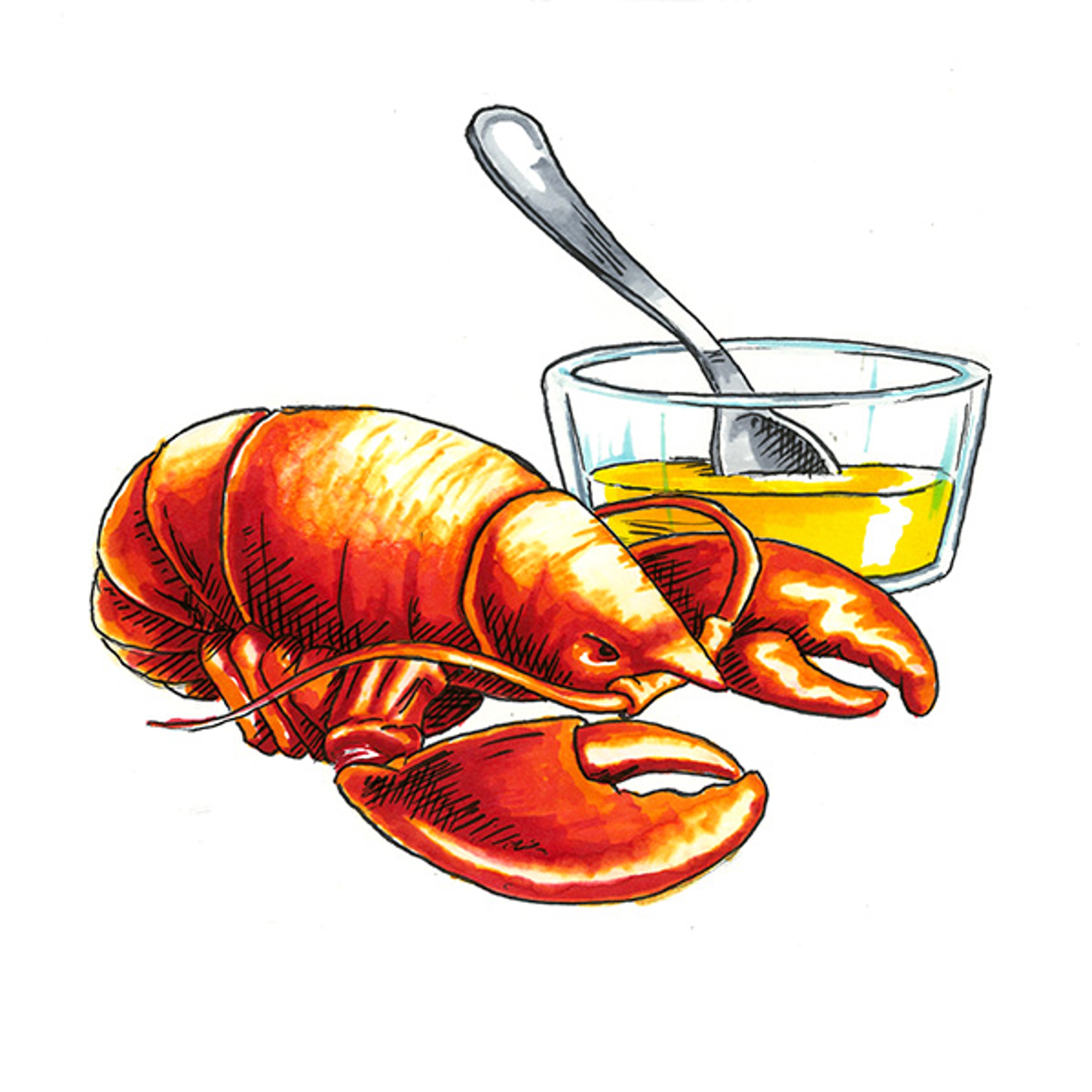

Make your own drawn butter

The best accompaniment to lobster is drawn butter. Simply melt 8 to 16 ounces of butter (4 to 8 servings) in a double boiler or in a heatproof bowl placed over a pot of water on low simmer. After about 6 minutes, remove the melted butter from the heat. When the butter has cooled slightly, skim the foam and solids from the top. Refrigerate the liquid butter and reheat it when ready to serve. The drawn butter can be refrigerated for up to a month.

Pairing wine with lobster

Like most seafood, lobster pairs best with white wine. Sierra Castellano, director of merchandising, Food, Wine and Stock Yards at Harry & David, says that many white varietals work well with lobster, but she'd recommend Harry & David Chardonnay, which is available as part of the White Wine Duo along with Harry & David Pinot Grigio. Castellano explains that the chardonnay “has a light oak presence with some weight on the back end of the palate, which complements most lobster dishes."

.svg?q=70&width=384&auto=webp)