Bread. It is a common fixture when it comes to everyday meals, a standard part of the weekly grocery list. It is a staple food of the general diet, providing nutrition including protein, iron, and fiber. It is what greets us as the unofficial first course at restaurants. Realtors even sometimes advise home sellers to leave a freshly baked loaf of bread on the counter, as the smell of it is associated with home sweet home. While bread has arguably never been known as a sexy food, it has become trendy in recent years, with a new generation of avid home bakers. A growing number of bread aficionados gather over bread tastings (yes, think wine tasting) that involve everything from sensory to crust quality and texture.

Despite bread being so popular and such a big part of our lives, do we really know that much about this ancient food? Maybe not. Let's change that.

The history of bread

While bread is considered part of the staple diet, its evolution is complex and involves technology, farming, and technique.

“Given the many steps involved in making bread, it is clear that bread is solely a human invention. It exists nowhere in nature," says Ken Albala, a food scholar, author, and professor at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California.

That said, bread has a rich history that goes back to the ancient civilizations spanning the West along with Mesopotamian cultures including the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Evidence exists, as written in Bread: A Global History, that hunter-gatherers made bread during the Stone Age some 22,500 years ago. In Asia, the earliest forms of bread — mantou and steamed buns made from wheat flour — are still a common part of everyday meals today.

Grain was already an essential part of the daily diet in early societies. The evolution of bread begins with grains, many of the ancient varieties; einkorn, for example — a type of ancient species of wheat — was the popular choice for dense bread, cakes, and porridge. The Greeks, on the other hand, preferred barley to make porridge and barley cakes. The various forms of bread were considered an important source of nutrition, especially with regard to protein.

Technology — specifically equipment — also played a critical role in bread making, as it does to this day. The flails for beating the grain out of stalks and sickles for cutting the grain have morphed into mega combines that cut the wheat, feed the wheat into threshers that shake grains from the stalks, and sort the grains from unwanted materials.

The same goes for how bread was milled. Water mills are an ancient Greek invention. The saddle quern technique of rolling over grains with an oblong rock, an essential for household milling operations, can be traced back to the Neolithic period (7000 to 1700 BCE). Stone milling then developed where the stones were turned with a handle or by a donkey, and became the primary way to turn grain into flour. Today, grain is harvested mostly with large farm equipment (combines), stored in granaries, and milled on a large commercial scale with industrial milling machines.

The evolution of bread

Turn the clock forward to the 19th and 20th centuries, and you'll discover a number of milestones that have contributed to the birth of modern-day bread commonly associated with a loaf. Packaged yeast, which first originated in the form of cube cakes in the 1860s, has made it easier for bakeries and home bakers to bake with ease. (Prior to packaged yeast, bakers often bought yeast from brewers.)

The development of patent flour (also known as very white flour) in the late 1800s is the result of millers refining the process of grinding grain.

“It was a moment where millers could refine flour to such an extent where they could separate the endosperm (the whitest part of the grain) from the bran and germ, and create a very white flour, and it changed the trajectory of baking and the way people think about bread," says Karen Bornarth, executive director of The Bread Bakers Guild of America. Bornarth notes that until then white bread and refined flours were a luxury and not readily accessible to the masses.

Another achievement in modern-day bread baking was commercial yeast, which emerged in the late 1800s, eventually overtaking the broad use of sourdough starters and beer yeast. Bornarth says this led to a "whole lot more consistency and predictability for bakers."

This was followed by another bread breakthrough: the invention of the Chorleywood bread process (circa 1961 in England). This was the product of a highly automated process that spawned loaves of white bread with a long shelf life. One of the most famous examples of this was Wonder Bread, which peaked in popularity in the 1970s and '80s. The progression of ovens — from stone hearths and earthenware vessels to industrial-scale ovens to the modern-day, state-of-the-art versions with a multitude of digital settings with self-cleaning cycles — has made the art of bread-making easy for non-bakers.

Sliced, sliced, baby

Sliced bread: Who would have thought it would take thousands of years for someone to figure this out? Otto Rohwedder, an Iowa inventor, developed the bread slicer in 1928 in Chillicothe, Missouri. This made it much easier to serve bread at all three meals.

“Sliced bread is more even. Sometimes people don't know how to slice it, and nowadays I think they take their chances with unsliced bread," says Jürgen Temme, a professional baker and former professor at the Culinary Institute of America. “When you have sliced bread, you have the better part, which is the end or the beginning of the bread, and you get more crust like that." This is the darker part of the bread and protects what is within. One centimeter, or two-thirds of an inch, is an ideal cut, Temme says — the perfect thickness for making a sandwich.

Is sliced bread really that great?

The late great comedian George Carlin joked about sliced bread, saying it wasn't so great. And, that after a couple hundred thousand years, this is all we have to compare things to. What about the Great Pyramids, Panama Canal, and the Great Wall of China he quipped. "Even a lava lamp is greater than sliced bread." He pointed out that all you need to slice bread is a knife. Here's our list of the greatest things that came before sliced bread:

Compass | Airplane |

Printing press | Automobile |

The nail | The wheel |

Light bulb | Optical lenses |

Internal combustion engine | Telephone |

Bornarth calls sliced bread “a very convenient kind of product. Bread being sliced and packaged improved the shelf life of bread," due to the addition of preservatives. An artisan loaf, as beautiful as it is, often goes stale faster once sliced. That's because these loaves, which, according to The Bread Bakers Guild of America, are "baked with intention" and not mass produced, do not include preservatives.

Six types of bread and their uses

The following recommendations were curated from a variety of professional bakers and sources interviewed for this piece. While there is a vast spectrum of bread, these six were chosen because they are either commonly consumed in the U.S. or represent how different cultures have their own unique twist on bread.

French baguette: Both savory and sweet, it can be eaten with cheese, cured meats, or butter. Considering it is hard and crusty, this bread is well paired with many kinds of soups.

Sourdough: Made from a starter, sourdough bread is great for homemade bread crumbs, breakfast sandwiches (e.g. avocado toast, eggs, and tomatoes), and French onion soup.

Rye: Pairs well with savory items, such as cold cuts, fish (note that rye is popularly paired with smoked mackerel), butter, and vegetables. Excellent for pastrami and Reuben sandwiches. Rye also works well with fruits and spreads with slight sweetness, such as almond butter.

Challah: Makes great French toast (some favorites include that which is topped with cream and fruits) as well as an assortment of desserts, including bread pudding, chocolate-cinnamon “Babkallah" (the not-so-mythical hybrid of challah-braided babka), and donuts.

Brioche: Similar to challah, brioche is stellar when toasted and particularly excellent for French toast, sandwiches, and burgers.

Pizza bread: The dough can be formed into a crust with a spectrum of texture and depth. Neapolitan-styled pizza is known for a thin, crispy crust often made with "00" standard flour from Italy.

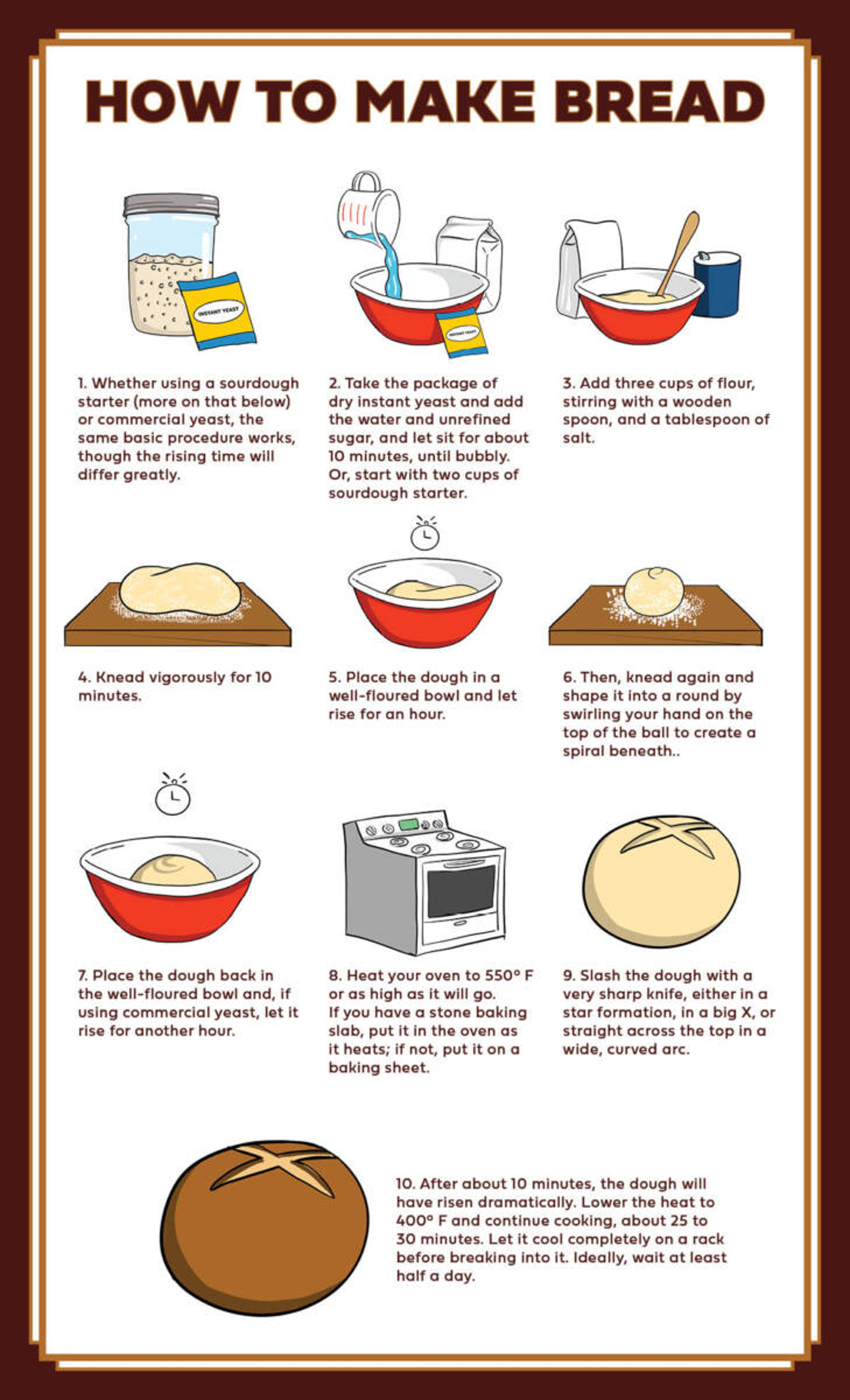

How to make bread?

The most basic bread recipe calls for only five ingredients...and time. The following bread recipe was contributed by Ken Albala.

Ingredients

- Package of dry instant yeast (not rapid rise)

- 1 cup of water (at 110° F)

- 1 teaspoon of unrefined sugar

- 3 cups flour

- 1 tablespoon of salt

What is a starter?

A starter is a leavening agent for sourdough bread that allows the bread dough to rise. The sourdough starter, also referred to as levain, is a fermented dough packed with wild yeast and a bacteria called lactobacilli. Wild yeast actually exists naturally in the air, but as you grow and cultivate the mix of water and flour left to ferment, it becomes a starter. The lactobacilli gives the sourdough bread a tangy flavor.

Truths behind multi-grain and whole wheat

"Whole wheat bread means that you are getting the whole grain in the bag. Whole wheat is the entire kernel, which includes the bran, germ, and endosperm. In the course of most modern-day milling, the three parts of the grain are typically separated and recombined to create whole wheat. If you buy a loaf of 'whole wheat bread,' this means that the bread contains some percentage of whole wheat flour in its formulation; that could be a very small amount," Bornarth says.

Multigrain bread features two or more types of grains and is often a medley of various grains, commonly barley, oats, rye, sunflower seeds, and buckwheat. Other additions might be cooked wheat berries, spelt, flax, and quinoa.

Both multi-grain and whole wheat bread contain fiber. Additionally, if the multigrain bread has whole wheat — any type of bread that contains whole grain kernel — it is considered nutritious since it is higher in fiber.

Dark flour and whole wheat flour that create the grainy whole wheat loaves have “gradually permeated the mainstream," writes scholar Margot Anne Kelley in her book Foodtopia: Communities in Pursuit of Peace, Love & Homegrown Food. The back-to-landers and hip bakers are contributing to this comeback.

Our favorite bread phrases

Bread is not only a popular part of everyday meals, but it often surfaces in everyday conversations, too. Here are some common bread phrases that were chosen by the various experts and sources that contributed to this article.

“The greatest thing since sliced bread." — This phrase means that something, often an invention or product, is good and useful. It was adapted from an advertising campaign by the Chillicothe Baking Company in 1928 to sell sliced bread.

“It's my bread and butter." — Phrase often used when someone is alluding to something they do for their livelihood. It was widely adopted in the 1800s as a reference to someone's job or income.

“I need to make more dough." — Dough is a slang word for “money" that has been popular since the 1930s. It is a direct reference to bread.

“The breadwinner of the house" — Defined as a family member who is the primary source of income or the sole provider of the family. It directly connects to the argument/idea that bread is a staple food and important for sustenance. Combine this with "bring home the bacon" and you have a great breakfast sandwich...

“They are toast." — This means that someone is ruined, defeated, and often destroyed.

"Man shall not live by bread alone." — A proverb that comes directly from the Old Testament and means that life should also include meaning such as spirituality beyond the basics of food and shelter.

.svg?q=70&width=384&auto=webp)